Bonnes adresses

A day with Christophe Vasseur, artisan-baker

" Fermentation is a wild animal that must be tamed. "

« They see the strong white arm knead

and shove the raw dough

Into the oven's bright hole.

They hear the good bread baking,

The baker with a fat smile

Growling an old ditty. »

Arthur Rimbaud,

Les Effarés

The interview took place in the laboratories of Christophe Vasseur, located above his bakery at 34 rue Yves Toudic in Paris (10th). I put my coat on a pile of flour bags called "Rouge de Bordeaux". During our discussion, Ako, one of the workers, was breaking eggs (at least 400 a day), while Sebastien, the pastry-maker(1) , prepared a batch of apple turnovers. A nice place for a meeting ...

Born in Moselle, Christophe Vasseur spent his early childhood in Alsace before his parents, doctors, settled in Annecy. After a degree in International Commerce and a first job marketing silk scarves in Asia, he "woke up" and began a second professional life. For the last fourteen years, he’s been up to his elbows ...

R&B In your book, you write that being a baker was a childhood dream. Why this fascination?

Christophe Vasseur: It's hard to explain. My first childhood memories are all related to food: cakes I was given, meals I ate, the snacks I had in day care as a young child, a pork butcher in Strasbourg who offered me a small slice of mortadella. I was influenced by this way of communicating via food. In fact, I am fascinated by what is eaten and what is shared. And what more beautiful symbol than a loaf of bread? It goes beyond feeding people with a dish that you have prepared or with bread; it is also a declaration of love or friendship. In his novel The baker's wife, Marcel Pagnol summed it up beautifully when he has his main character say: "I'm going to make you a loaf with love and friendship baked in. " It’s all there ! I think winemakers have the same carnal relationship with their vineyards and with their wine; their wine is an expression of their terroir, but also of their individuality and sensitivity.

I chose this means of expression at an early age. I could have become a cook, but the dough is really the basis for a meal and, though I’m not doused in holy water, there may be a distant relationship with religion. In addition, my name is Christophe (Saint who carried Christ – Editor’s note) ...

R&B And after fourteen years?

C.V. : Working the dough and coaching the people on my team - thankfully I'm not all alone - those pleasures remain intact. I’m not at all worn down or tired. I still find it beautiful and hope I will never stop feeling this way. Even when I’m old and riddled with rheumatism, I'll make bread on Sunday in my wood-burning oven and invite my friends over. Sitting together to dine is to surround oneself with people we love; we talk, we laugh, we sing, we cry, we argue sometimes, but we fraternize, which represents humanity for me!

R&B You mentioned that wheat has grand crus, just like wines. Can you expand on this ?

CV: I'm not expert enough to talk about the wheat characteristics the way you talk about grape varietals

Of course, I know the strains of wheat in our current flour mix. Right now, we are using Rouge de Bordeaux, an old red wheat strain, grown on the Duroc farm in Seine-et-Marne. It is called Rouge Duroc, because while originally from Bordeaux but now being sown on a terroir that is not Bordeaux, it gives a taste different from the same strain grown in Bordeaux. This is normal because it is the expression of the earth, sunshine, precipitation, in short a microclimate.

Unlike a winemaker, I don’t own land, and thus have not sown wheat. On the other hand, Roland Feuillas (2) could tell you that his flours come from the black wheat of Iraq, Rouge de Bordeaux or Barbu du Roussillon. I just ask my millers, Les Moulins Bourgeois, to find me the most delicious, tastiest varieties, those that develop the most aromas. I try to have my breads full of aromatic complexity. Even if 100% of my flours currently come from the same mills, I’m not stuck in place. When I meet farmers who grow old varieties of wheat, I often test these flours to increase my knowledge. It should be noted that Les Moulins Bourgeois have an environmentally aware approach, they not only encourage their suppliers to produce organically, but they also try to convince them to replace their varieties of modern wheat with old varieties. It's not easy for the growers because the yields are lower and the price is higher, but the taste is fantastic, not to mention the digestibility ...

R&B Why use yeasts rather than sourdough ?

CV: The sourdough approach is a bit like"Parker style" barrel aging. The result is monolithic. When I was starting out, I used two lovely and very different flours, I made sourdough bread from both, and I realized that the two loaves had the same taste. It is certainly a powerful taste, but lacking complexity, and with high acidity. Don’t forget that historically the use of sourdough was intended to mask the flaws of the flour. For a very long time, a wheat harvest would include other plants that sieving did not eliminate. Thus, when everything was milled, the taste of the flour tended to be distorted. To erase these defects, bakers used sourdough, which is a fermentation that has already reached the peak of its maturity curve. However, if one delays too much, after a few hours, the sourdough turns to acetic acid, vinegar. This acid aspect gives the illusion of character and taste, a bit like when you drown the foie gras with port when making a terrine. For me, the expression of a flour must be much subtler. The quantities of yeasts I work with are very small: I use less yeast than any of the bakers who work with sourdough: they add two to three grams of yeast per kilogram of sourdough, while I use less than two grams per kilogram of flour. As in winemaking, yeasts are mushrooms that belong to the Saccharomyces family. By starting the fermentation with so little yeast, I enable the wild ferments that are part of the flour to express themselves. But too much added yeast kills these wild yeasts. Of course, the bread will rise anyway, but it will be dry, tasteless and, to top it off, indigestible.

Low doses of yeast awaken the native yeasts in the flour, and gives them time to develop, the result is completely magical. It's the same for wine: there are intimate links between winemaking and bread baking: fermentations, use of temperature and interaction with the natural world.

R&B Are your fermentations longer?

CV: My fermentations are slow and long: they last two days. It's common sense; we let time do its work.

One tragedy of our modern world is that “time is money”, it leads to forgetting the fundamental principles, that is to say health, taste ...If we rush things, we have to use chemical crutches. To make good bread, it is necessary to control the fermentation, its temperature and duration and then the baking. Even with good flour, if you do not master the process, you will never get a good loaf. It is like the winemaker who harvests beautiful grapes, but who does not master his winemaking. In addition, I develop an aromatic palette that is beyond comparison with sourdough breads, or "modern" breads that are made in two hours. Finally, there is a step, absent in the winemaker, baking. A successful bake gives a bread with a thick crust, roasted but not burned. All the art is to get this toasted crust without drying or burning the bread.

R&B What solutions do you adopt for controlling the fermentation, the step you call “the key to taste" ?

CV: Fermentation is a wild animal that one must tame; we never master it completely, but we manage to channel it and bring it where we want to go. There can be no total control, because depending on the weather, hygrometry, temperature - and even at equal temperature and hygrometry -, the flour that I will receive this week is not quite the same as that of last week: it is alive. This is why we must remain humble. Everything is based on observation. Very quickly, as soon as the water is poured and we begin to mix, we see how the flour drinks, quickly or slowly. Does the glutinous network become smooth quickly or slowly? So, we adapt. We take the temperature. Does it correspond to the desired temperature or not? We then do a first fermentation for fifty minutes and can see if we’re off to a good start. Depending on these results, we adapt the recipe. We do another test period, a little longer, a little shorter. All this is part of the joy of baking, because it is never the same. We really feel like we’re interacting with a living thing. It's not dead dough!

R&B Do you have any manufacturing secrets that you cannot share ?

CV: Yes, I have a manufacturing secret that I do not disclose. We have our recipe, our know-how: thus, the Le Pain des Amis (Bread for friends), our emblematic house bread, has a taste that nobody today can duplicate. And that's good, because for me every craftsman must be able to create an individual, unique product.

R&B Tell me more about flour

CV: I use live flours. Without life, there is no taste. Of course I am against using any “chemical crutches”. Take a moment to read the ingredients of a bag of industrial flour, including the list of additives: they include anti-oxidants, flavor enhancers and all sorts of magic powders, just to compensate for the fact that there is no life left in the product.

R&B You favor a short kneading time?

Yes, because the more you knead, the more you incorporate air. You need just enough air to ensure fermentation. If there is too much, the dough will be oxidized. Here again, you can see the parallels with winemaking.

R&B As part of breadmaking, what do you check on ? On which ingredients?

CV: I send my different products - apples, flours ... to laboratories for analysis. The water is filtered - as for coffee or tea - because if you want a product with taste, it is essential. Filtration eliminates chlorine, limescale, lead and heavy metals, thus allowing us to reduce the doses of salt and yeast. The water does keep its trace elements. We use sea salt in our breads.

R&B In your book, you talk about problems with gluten

CV: There is a lot of misinformation about gluten, and this helps companies who want to market gluten-free products. The basic problem is not the presence of gluten, since it has been consumed for centuries and people have gotten along fine. In fact, the problem concerns gluten from modern wheat, these cloned varieties – almost like OGMs - that we are made to eat today. Looking at wheat fields over history, you would notice that the plants have become smaller and smaller. If you look at harvest paintings from past centuries, you will notice that the wheat was as high as a man. In trying for higher yields, the plants were bred to reduce the proportion of straw (stalk). Thus, the gluten molecule has gotten bigger and since the fermentation time of the dough has also been reduced, the gluten molecules don’t breakdown enough and the bread becomes indigestible. It's not a fad, it's a reality: if gluten intolerance is increasing, it is because, 99% of the time the bread is made in two hours with modern wheats, it is indigestible! With organic flours and long fermentations, there are no problems of digestion, bloating or even rashes. I see this all the time with my customers.

R&B You are critical of industrial pastries (Viennoiserie) ?

CV: 85% of viennoiserie (croissants, etc.) is manufactured industrially. Not only flours of s ... (unprintable) are used, but the croissant is made in two hours on an industrial production line, not in 36 hours (as it should be). To produce at this speed, flour like ours can’t be used because it resists. It's like a muscle. If you try to roll out our flour, fold it and roll it again, it's impossible, it splits apart. To get around this, industrial pastry manufacturers add softeners, just like for laundry.

There are many chemical crutches that can over-mechanize the process, make it go more quickly, and try to make the taste less insipid. Beta-carotene, flavor enhancers, monosodium glutamate, palm oil are all added to give the illusion of some aromas, These are unhealthy fats, and when sugar is added, it is poor quality sugar (or glucose), and it’s all undigestible. The worst is that there is a total omerta (conspiracy of silence) about this problem. The public authorities don’t want to take notice, because bread is sacred. No one talks about it; the journalists are discouraged by a French oversight organization: the Bread Observatory (l’Observatoire du Pain). The pressure groups of the bread industry do their utmost to suppress objective information. I think there is a real health scandal involving bread and pastries.

R&B Have you inspired others (bakers) ?

CV: My concerns are taste, consumer health and the impact on future generations. But I have long felt like I’m preaching to an empty room. I can live with this because I feel that I’m doing my part. If I can make people a bit more aware, if consumers change their eating habits a little, or if fellow bakers start to analyze their flour, I will, as Pierre Rabbi says (3) , have done my part! It's not a huge step, but if, over time, a group of us are all working in this direction, the world will be better for it!

R&B How many of you have this approach to making bread?

CV: Talking about “artisan bakeries” doesn’t mean much anymore. I can’t think of another Parisian baker who works like me. There are only a handful of us in France, but I hope that with time we will be a little more numerous. I do not know anyone who is worried about the composition of their raw materials. Whenever I meet reputable pastry chefs, go into their back shop, see their stocks of glucose syrup and palm oil, and comment on them, I get looked at like I’m insane. They do not believe me. People don’t like getting shaken out of their comfort zone. As long as there is no law prohibiting palm oil and glucose syrup, this mechanism for producing diabetics will flourish. We’re producing diabetics just like in the United States. Glucose syrup is everywhere, in both sweet and salty products. Unfortunately, your liver and pancreas do not metabolize it. Maybe it’s because I’m a doctor's son that I see the health implications of the products I use. Maybe that’s the reason I feel responsible. In any case, I can’t just close my eyes to the problem and pretend that everything is ok because these practices within the law.

Like good bread

Le pain de la terre à la table Christophe Vasseur Editions Du Pain et des Idées, 2016

Homer refers to men as "bread-eaters" and opposes them to the gods who live on nectar and ambrosia. Later, Judeo-Christian theological precepts associate bread and wine, the symbolic food and drink. The solid and the liquid complement each other and have many similarities. Christophe Vasseur, master baker, invites us in a beautiful book to (re) discover the flavors and benefits of real bread.

This is a book full of nourishment. It's first of all a book about meetings with characters who have deeply influenced Christophe Vasseur. In its pages, we meet Roland Feuillas, the "knight of real bread, raging against all those who torture the land and the stomachs", Erik Rosdahl, who cultivates vineyards in the Murcia region of Spain, Clément Bruno, a truffle-loving chef, and Steven Kaplan, "the pre-eminent historian of the wheat-flour-bread" segment. But it's also a cry of anger over the disappearance, in just over a century, of two-thirds of the varieties of common wheat. Only 330 remain in the official catalog of wheat and those fit for bread-making; the top ten varieties cover 44% of French wheat fields and more than half of farmers sow only one or two different wheats. Even more serious, the old varieties are too numerous to describe and the cost of adding them to the catalog is prohibitive... Now that modern, cloned, hybrid wheat rules the roost, "the wealth of our seed heritage is being lost in favor of industrial standards, and at the expense of our dietary diversity and our health," insists Christophe Vasseur. Ten multinationals now control 75% of the global seed industry market! It is therefore not surprising that organic flour represents only 1.5% of the French market. These organic flours are of course part of the raw materials used by the uncompromising Christophe Vasseur for the making of his breads and pastries. He makes his bread with intense pleasure and extreme rigor: soft kneading, very long fermentation (48 hours) and baking adapted to each batch, and it gives bread that is tasty, nourishing and easily digested. My goal is to give pleasure to people with something I’ve made with my heart, guts and head, " he writes. The book is also full of statistical data and historical, legal and scientific information about bread, of course, but also about its ingredients. The last part is dedicated to bread and pizza recipes. We also appreciate the sage advice on how to choose good bread.

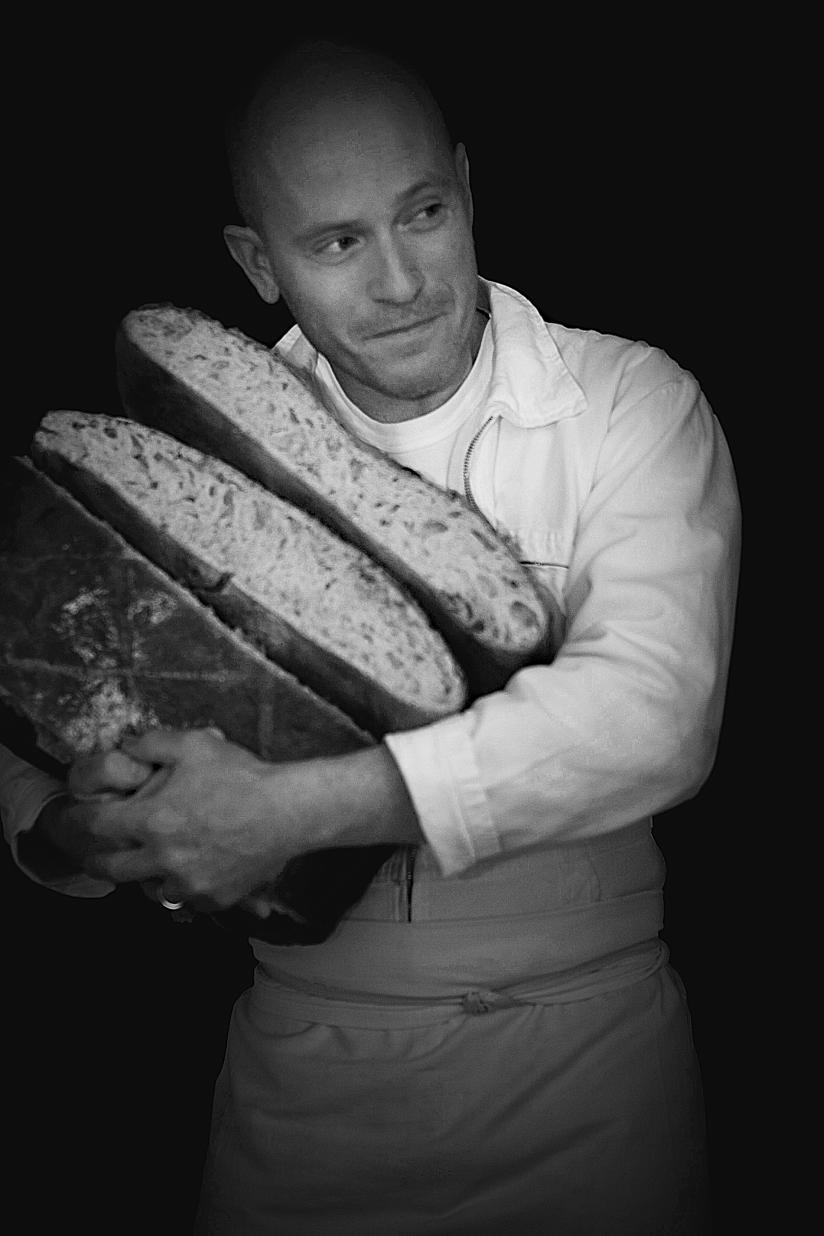

Benoît Linero's full-page photographs are sublime and almost ... fragrant. Christophe Vasseur wanted to tell a story through the emotions generated by the photos. He succeeds beyond all expectation; one leaves his book reluctantly with a sated spirit and a healthy appetite.